Artigo Completo

Grammar teaching and digital learning: didactics with creativity and gender

Ana Sofia Lopes

Universidade de Santiago de Compostela/ Escola Superior de Educação do Politécnico do Porto

Celda Morgado

Escola Superior de Educação do Politécnico do Porto/ CLUP - Centro de Linguística da

Universidade do Porto/ InED - Centro de Investigação e Inovação em Educação

ABSTRACT

In language teaching, the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) have positive implications, because these are a pedagogical strategy to develop the components of text comprehension and these are a contribution to the grammar teaching. If today technologies are part of children's daily lives, teachers can not ignore the challenges that this digital generation brings, and should make didactic use of ICT. Thus, a didactic sequence was developed in the 3rd grade of the Primary School, in which ICT contributed to linguistic reflection and comprehension around verbal situations and grammatical gender. The goal of the sequence was the construction of a digital book composed of texts about imaginary animals resulting from a mixture of different texts and a script of linguistic comprehension and reflection, in which the students classified the verbal situations expressed by the verbs used in the texts. The students proceeded to assign the sex of the animals originated from the mixture of texts. The data gathered reinforced that the study of verbal situations contributes to the development of reading comprehension, that there is a confusion between grammatical gender and biological sex, and that the use of ICT are a motivational factor in teaching and learning processes.

Keywords: information and communication technologies; grammar teaching; reading comprehension; verbal situations; grammatical gender

1. INTRODUCTION

Today, we live in a society where technologies are an integral part of everyday life, i.e., in a digital age (Ponte, 2002; Flores, Escola & Peres, 2009). In this society, the human being is confronted with new and different ways of reading, dominated by different languages and codes, namely verbal, visual, audio and computer; as well as multiple media, namely print and digital, that influence how one understands and interacts with texts. Thus, a new reading subject is now required, benefiting from teaching and learning processes centred on the acquisition and development of 21st century skills (Plano Nacional de Leitura, 2017). These competences will help the reader to be able to master the multiple literacies of the informational and media environments which surround him. Therefore, it is in this context that the Portuguese teacher assumes special relevance because reading (and writing) is a "componente chave transversal"[1] for the development of the above-mentioned competences (Plano Nacional de Leitura, 2017, p. 22). The Perfil dos Alunos à Saída da Escolaridade Obrigatória (Oliveira Martins et al., 2017) emphasises the importance of students acquiring the multiple literacies which enable them to analyse and question reality critically, evaluate and select information, formulate hypotheses and make decisions based on daily life.

According to the above, teachers, in order to respond to the complex challenges of this century, must rethink their practices and adapt them to the reality and the current context. According to the Decree-Law no. 6/2001 of January 18 and the Perfil dos Alunos à Saída da Escolaridade Obrigatória, it is essential that teachers seek to develop educational practices in which students are offered a unified vision of knowledge that, in turn, enables a rapid retrieval of information, a growing motivation throughout learning, and a meaningful learning process, because meaning is given to a contextualised reality (Pombo, 2005; Leite, 2012). It is also important that teachers integrate ICT as didactic means, because these are a pedagogical strategy to motivate and develop the different components involved in understanding texts (Viana et al., 2010) and these are a contribution to the grammar teaching (Mateus et al., 2003); as well as to make use of updated scientific and pedagogical knowledge when choosing and/ or drafting strategies, choosing and/or constructing didactic materials and adapting the information required by the complexity of the content and skills to be acquired of the students, due to the unequal rhythms and learning styles (Leal, 2009).

In structural terms, this text is divided into two main parts, in addition to the introduction and conclusions. In the first one, the contribution of grammar teaching to the development of reading comprehension will be evidenced, focusing, at the level of the word class verb, on the typology of verbal situations, and, in terms of the word class noun, in the category nominal gender. In the second part, a didactic sequence developed in a group of 3rd year of schooling, of a grouping of schools of the district of Oporto, involving the mentioned grammatical contents, in the service of the reading comprehension, and the ICT like pedagogical strategy.

2. FROM THE GRAMMAR TEACHING TO READING COMPREHENSION

The knowledge that students are building about their own language proves to be important for the development of reading comprehension, because it corresponds to a complex phenomenon involving different linguistic processes, from the sound level, the word level to the text level; and cognitive processes, namely the intervention of the memory system, coding processes and inferential operations based on prior knowledge and situational factors (Ribeiro et al., 2010; Lencastre, 2003; Perfetti, Landi & Oakhill, 2005; Cain & Oakhill, 2009). There are studies, such as that of Leal and Roazzi (1999), which, in syntactic and semantic terms, point to the fact that linguistic awareness plays an important role in reading, namely in comprehension.

In this context, we present the different components involved in reading comprehension: literal comprehension, which consists in the reader's recognition of ideas, information or events expressed linguistically in the text; the reorganising comprehension, which concerns the systematisation, schematisation or summary of the nuclear information, consolidating or reordering the ideas through the information that it obtains, so as to achieve a comprehensive synthesis; the inferential comprehension, which corresponds to the activation of the prior knowledge of the reader and to the formulation of anticipations or assumptions about the content of the text (or part of it) through the indications provided by the reading; and critical comprehension, which consists in formulating judgments about the content of the text and how it is expressed (Viana et al., 2010, Giasson, 1993).

2.1. PROBLEMATIZATION OF THE VERB AS A WORD CLASS AND VERBAL SITUATIONS

The verb, which creates “uma predicação semântica e uma predicação sintática acerca de uma entidade - o sujeito”[2] (Choupina, 2015, p. 356), is an open and variable class of words. Having the lexical and nuclear meaning in the semantics and syntax of the sentence and being the nucleus element of the group or verbal syntagma, the verb plays the syntactic function of predicate (Duarte, 2003) and corresponds, in natural languages, to a word predicative par excellence (Duarte & Brito, 2003, p. 183).

In relation to this class of words, it is important to refer to the argumentative structure, a semantic-lexical notion that involves the following aspects: number of arguments required by the verb; categorical realisation that the verb specifies for each of its arguments; and thematic role or semantic function that attributes to each argument required by the verb (Duarte & Brito, 2003). Regarding the last aspect, it corresponds to the semantic relation that associates the argument with the predicate word that selects it. Therefore, when the semantic properties of the verb are not respected, the sentence becomes agrammatical, even if the aspects previously enunciated are respected (such as *Rain scared the windows). In this way, it is necessary to take into account the thematic roles relevant to the description of the argumentative structure of Portuguese verbs, whose minimum list includes the roles of Agent, Source, Experiencer, Locative, Target, Theme, Beneficiary, Patient and Cause (Duarte & Brito, 2003; Gonçalves & Raposo, 2013), as well as the semantic entities that can perform them (in the given example, the constituent windows can not draw the function of Experiencer). Let us go on to exemplify and explain some of them, from examples collected in books such as Meninos de todas as cores by Luísa Ducla Soares (2010) and A Minha Primeira República by José Jorge Letria (2009), when teaching in school years in which these works are approached (Lopes, 2018):

-

“Era uma vez um menino branco, chamado Miguel, que vivia numa terra de meninos brancos (…).” (Ducla Soares, 2010, p. 2)

Once upon a time there was a white boy named Miguel, who lived in a land of white boys - “O menino branco foi correndo mundo (…).” (Ducla Soares, 2010, p. 5)

The white boy has been running the world - “Paiva Couceiro e as suas tropas foram travados no cimo do Parque Eduardo VII (…).” (Letria, 2009, p. 26).

Paiva Couceiro and his troops were caught at the top of Eduardo VII ParkIt should be emphasised that the subject present in 1) plays the thematic role of Theme, because it is designated as a non-controlling entity or experiencing a non-dynamic situation (Duarte & Brito, 2003). Already in 2) an Experiencing subject occurs, given that it is designated an entity that changes through an experiment (Melo, 2017). Finally, in 3) there is a Patient subject, because it designates an entity affected by a situation that is described, as well as a Locative complement ("at the top of Eduardo VII Park"), since the space location of an entity (Duarte & Brito, 2003). Regarding this last example, it should be noted that the sentence is in the passive form, having a subject Patient. This was not the case if the phrase was in the active form, since the subject would come to play the thematic role of Agent, because it is a controlling entity of a situation (Cunha, 2004).

In view of the above, it becomes clear that the number and nature of the arguments of a particular verb are closely related to its aspectual nature, depending on the type of situation that the verb and its arguments can express. Therefore, if, on the one hand, there are verbs that occur in non-dynamic situations, on the other, there are verbs that occur in dynamic situations. In the first case, the verbs occur in situations that express states, in which the entities do not change in the period of time of occurrence of the situation; in the second case, there are changes to the entity (Duarte & Brito, 2003; Cunha, 2004). For a better understanding of the mentioned typology of verbal situations, excerpts from "O mercador de coisa nenhuma" by António Torrado (1994) are subsequently presented.

Verbs that occur in non-dynamic predicates - “Era respeitado como um dos homens mais ricos da cidade e um dos mais felizes.” (p. 3);

He was respected as one of the richest men in the city and one of the happiest. - “Eu tenho nestas caixas grãos azuis, pretos, amarelos, brancos e transparentes.”

(p. 6)

I have in these boxes blue, black, yellow, white and transparent grains.

Verbs that occur in dynamic predicates - “Carregou duas grandes caixas de areia fina para as portas de uma cidade e começou a apregoar.” (p. 6);

He carried two large boxes of fine sand to the gates of a city and began to proclaim - “Racib contou um sonho lindo (…).” (p. 7).

Racib told a beautiful dream…

In terms of verbs that can occur in non-dynamic predicates, it is noted that, according to Vendler (1967), quoted by Rothstein (2008), in this group, expressing states, one can include: existential verbs (such as “to exist” and “to be”); locative verbs (such as “to live”); possession verbs (such as “to possess” and “to belong”); epistemic verbs (such as “to know”); perceptive verbs (such as “to see”); non-causative psychological verbs (such as “to like”); and copulative verbs (such as “to be” and “to stay”). In turn, in the case of dynamic situations, according to the same author, it is possible to distinguish verbs that express: activities (unbounded processes, such as “to smile”); accomplishments (bounded processes, such as “to buy”); semelfactives (instantaneous atelic events, such as “to knock”); and achievements (point events, such as “to start”).

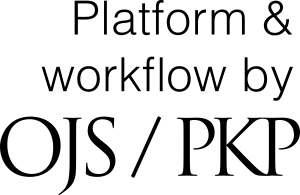

In order to summarise, we present table 1, which brings together multiple verbs, grouped by the predicates in which they occur - not dynamic and dynamic - as well as the thematic grid associated with them.

2.2. GENDER AS A NOUN PROPERTY

According to Brito (2003) and Duarte and Oliveira (2003), the noun is an open, variable and universal word class to the world's languages, corresponding to a linguistic category that can be semantically characterised by having a reference potential. Therefore, it is usually used in a concrete situation of communication, with a designation or appointment function. This class of words, which is the nucleus of the Nominal Syntagma (SN), "allows variation in gender, number and, in some cases, degree" (Dicionário Terminológico em linha, B.3.1.). In this subsection, only gender will be highlighted, since it was the nominal category emphasised in the didactic sequence that will be described in section 3.

In European Portuguese (EP), gender consists of a mandatory nominal category for morphosyntactic concordance in phrases and sentences (Baptista et al., 2013), and in this language all nouns have a gender value - male or female - independently of its lexical or syntactic attribution, which materializes in the syntax of the language, namely in the mechanisms of concordance (Choupina, 2017). In addition, gender plays several linguistic functions, namely: syntactic, because it signals concordance, structuring the whole SN and clarifying the relations; semantic, since it sometimes allows the distinction of meaning in pairs “o banco” (as a seat)/ “a banca” (as a financial organisation); and morphological, since it determines the internal structure of certain words, as determinants, adjectives, quantifiers and pronouns (Gouveia, 2004).

Assuming gender as an unsystematic and synchronically arbitrary category, which is not flexional (Villalva, 2003) in the EP, there are several morphosyntactic processes that allow the formation of words and, consequently, the specification of the gender value of nouns and, sometimes the construction of the "illusion" of gender alternation or contrast: marking of the thematic class, carried out by the thematic index (-o, -a, -e e Ø/atemático), as in menino and gato; phonological alternation, as in irmão and irmã; derivation, in examples like conde and condessa, cão and cadela; and syntactic processes, o estudante and a estudante. These processes exclude those known as the composition of male and female (such as male elephant and female elephant) and lexical contrast (as ox and cow), since the nouns that illustrate them are inherent gender and only contrast the sex of the referents named by these nouns (Villalva, 2003; Baptista et al., 2013, Choupina, Baptista & Costa, 2014, Choupina et al., 2016).

With regard to the two morphosyntactic processes highlighted above, it should be noted that it is often the case in the EP that a relationship is established between linguistic gender and sex. However, gender and sex do not present an intrinsic relation to each other, that is, “o género é uma categoria arbitrária e, por isso, não estabelece correlação com a noção de sexo”[3] (Costa & Choupina, 2011, pp. 3-4). On the one hand, it refers to a grammatical category (gender) and, on the other hand, a biosocial reality (sex). The following examples illustrate the lack of correlation between gender and sex.

8. a) mulherão (noun male gender and female sex)

‘woman+fixed morpheme –ão’

big woman, very beautiful woman or very sensual woman

b) rapaziada (noun female gender and male sex)

‘boy+fixed morpheme –ada [collective noun]’

boys group

9. a) tigre-fêmea (noun male gender and female sex)

‘tiger-female’

female tiger

b) baleia-macho (noun female gender and male sex)

‘whale-male’ male whale

This confusion lies in the fact that for both categories the same forms of designation and distinction of the values or categories in which they take place - male and female - apply; as well as considering that “o sexo biológico funciona como motivação para a atribuição do valor de género"4 (Costa et al., 2015, p.329). Even the term gender corresponds to a polysemic term and therefore applies to very different realities. This may arise as a synonym for sex or biosocial identity, as well as to refer to a morphosyntactic category in the context of linguistic metalanguage (Baptista et al., 2013). Considering the above, and considering the teaching of this nominal category, its approach should not promote the production of contrasts. Therefore, it is argued that the approach of the category biosocial sex must be done separately, in a proper moment, within the scope of the Study of the Environment5, as already advocated in Lopes, Choupina and Monteiro (2017).

3. APPLICATION TO THE PORTUGUESE TEACHING IN THE PRIMARY SCHOOL

At this point, we will describe a didactic sequence, entitled Mixed, Classified and Fractionated Animals, developed (by the first author) in a group of students of the 3rd grade of the the Primary School, of a School Group of the district of Oporto. In the above mentioned didactic sequence, as the title indicates, the animals were the guiding thread of all classes. Summarily, and according to Lopes (2018), the pupils undertook an activity of mixing animal poems in Portuguese, and drew the resulting animals in Plastic Expression (Mixed Animals); they classified the animals as vertebrates or invertebrates, as well as did their classifications for feeding, reproduction, habitat and the environment in which they move, in Study of the Environment; and in Mathematics, they performed tasks centred on the content of the fractions and the classifications of the animals, which they learned in Study of the Environment (Fractionated Animals).

Therefore, it is possible to affirm that, in the didactic sequence, the articulated construction of knowledge was promoted, as well as the sequential development of students' learning, through the establishment of relations between the different curricular areas and their contents (Leite, 2012). In this way, we sought to break with a piecemeal logic that in no way facilitates the formation of citizens for a knowledge society (Roldão, 1999) and, on the other hand, offer students a unified view of knowledge. Thus, a faster retrieval of information is possible, a growing motivation throughout the learning process and a meaningful learning process, since it is given meaning to a contextualised reality (Pombo, 2005; Leite, 2012). This is also a principle patented in legal documents, namely Decreto-Lei no. 6/2001 of January 18, article 3 of which points out that one of the guiding principles of organisation and management of the curriculum corresponds to “existência de áreas curriculares disciplinares e não disciplinares visando a realização de aprendizagens significativas e a formação integral dos alunos, através da articulação e da contextualização dos saberes”[6]. Also in the Perfil dos Alunos à Saída da Escolaridade Obrigatória, it is emphasised that learning is guaranteed through a coherent and flexible educational action, that is, through the flexible management of the curriculum and the teachers' cooperation work on the curriculum (Oliveira Martins et al., 2017).

3.1. FROM TYPOLOGY OF VERBAL SITUATIONS TO READING COMPREHENSION

Although several activities have been carried out in the highlighted teaching sequence (see Lopes, 2018, pp. 79-80), in this subsection and in the subsequent one, we will focus only on those developed in the area of Portuguese and the cooperation that was promoted with ICT.

Thus, it should be emphasised, first, that the activities developed around poetic texts, namely poems collected in the literary books Fala Bicho by Violeta Figueiredo (1999), O Alfabeto dos Bichos by José Jorge Letria (2005), Bichos Diversos em Versos by António Manuel Couto Viana (2008) and Aquela nuvem e outras by Eugénio de Andrade (1999). At first, the teacher read two poems - "Elefante" [elephant] from the book O Alfabeto dos Bichos by José Jorge Letria

(2005) and "O Cavalo" [the horse] from the book Bichos Diversos em Versos by António Manuel Couto Viana (2008) - and afterwards aimed at their comprehension. For this, a survey was made of the characteristics of the animals on which the poems were written, both in literal and inferential comprehension (Viana et al., 2010; Giasson, 1993), and later these characteristics were recorded on a table. In order to achieve comprehension, a linguistic reflection in the level of the referential cohesion was also undertaken, since the students identified the referents of the clitic pronouns -lhe and -o and, subsequently, they replaced the pronouns by the referents that they identified initially. Afterwards, students reread the poems and, even before the teacher questioned them about the differences between the use of nominal anaphoric retrieval mechanisms (by reiteration) and the use of pronominal anaphoric retrieval mechanisms, they immediately stated that when the pronouns were replaced by their referents, the poem became repetitive.

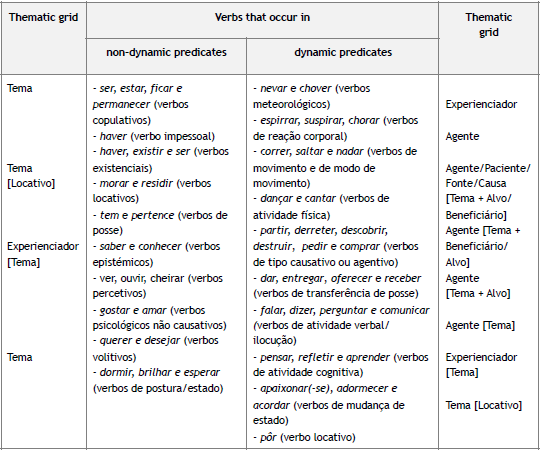

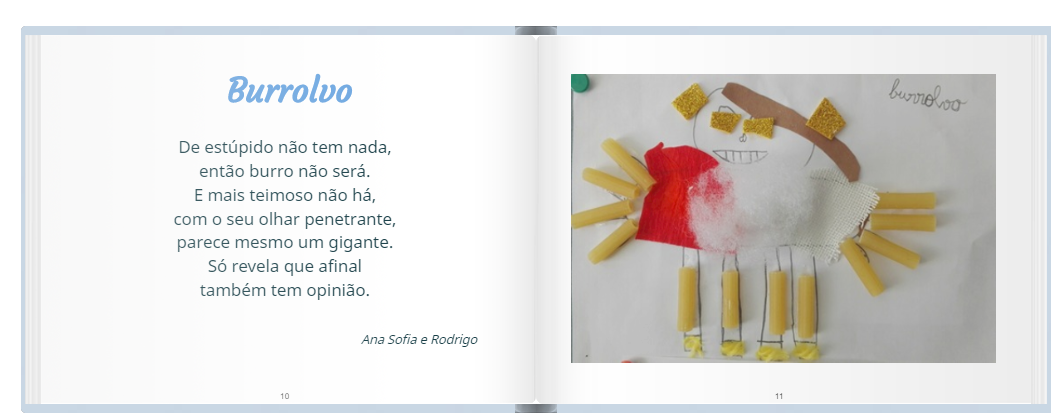

Another activity, and the one that deserves greater prominence for incorporating ICT, was developed based on a creative writing activity, starting with poems from the books already mentioned. This consisted of a mixture of texts, namely two poems about different animals, so that students, organised in small work groups, could create a new text and, consequently, an imaginary animal. Therefore, the activity motivated the creation of neologisms to designate them, such as giramiga, burrolvo, tubaraco, camedo, fonhoca, jacapardo, pembra and dorinha, created by the irregular processes of truncation and amalgam. With the new text, each group proceeded to survey the characteristics of the imaginary animals, with special emphasis on the verbs that specified the situations associated with each animal, in order to understand the profile of this unique referent recently created. All this work gave rise to a digital book[7], created in the tool StoryJumper. The first part is composed by the new texts elaborated through the mixture of poems, the reading of the same by the pupils and the illustration of each animal created within Plastic Expression (see Figures 1 and 2); while the second corresponds to a script of comprehension and linguistic reflection, which includes the verbs that the students emphasised of the new texts and the classification they made of the situations created by them, thus grouped in dynamic situations or non-dynamic situations.

In this activity, the students revealed a more consistent knowledge in the identification of verbs and in the classification of the situations created by them, compared to the first activity developed around the typology of verbal situations, with "O mercador de coisa nenhuma" by António Torrado (1994). However, they have also demonstrated some difficulties in identifying the type of situation in verbs that do not properly express an activity, such as liking, regretting and preferring. According to Vendler (1967), quoted by Rothstein (2008), these are psychological verbs within non-dynamic situations. It is considered that the confusion generated with this type of verbs is due to the fact that they are verbs that integrate in their meaning a mental state, and are therefore difficult to understand for the students within this level of education, because they require a more abstract thinking and a greater reflection for its classification. In addition, it should be emphasised that in the activities carried out around the verb, dynamic verbal situations seem to be favoured in all years of schooling, as evidenced by data collected in school course books of this area of knowledge (Lopes, 2018), which contributes even more so that students have difficulty in classifying verbs that occur in non-dynamic situations.

Figure 1 - Poem and illustration concerning the imaginary animal burrolvo

(Source: https://www.storyjumper.com/book/index/50722776/AnaSofiaLopes)

Figure 2 - Poem and illustration concerning the imaginary animal giramiga

(Source: https://www.storyjumper.com/book/index/50722776/AnaSofiaLopes#)

It should also be mentioned that the activity that has been described and analysed has contributed to the harmonisation between the components of literal and inferential comprehension, since, with the construction of the digital book, especially with the elaboration of the script of comprehension and linguistic reflection in that the verbs were surveyed, the students were able to recognise and infer some of the characteristics of the imaginary animals they created. Simultaneously, this activity witnessed the integration of ICT in the teaching and learning processes of students (Ponte, 2002), which is essential in today's society, a society of the digital age. Such integration constituted, on the one hand, a new possibility for students to experience a creative process; and, on the other hand, a motivational factor which favoured a growing involvement and understanding in learning.

3.2. FROM NEOLOGISM CONSTRUCTIONs TO BIOLOGICAL SEX CATEGORY ATTRIBUTION

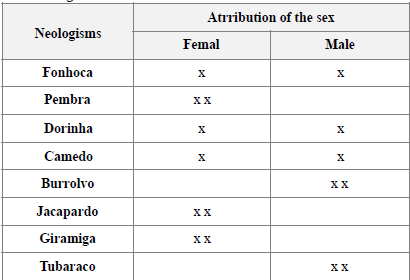

After having undertaken the above activity, each of the elements of the various working groups was asked to assign the sex category of referents named by the created neologisms. This assignment occurred in an individual way, contrary to everything that has been done so far by the students, because it was intended to analyse the representations and personal knowledge developed in what refers to the nominal gender category.

Thus, according to the data presented in table 2, it was found that in five of the eight work groups, the students attributed the sex category based on the gender value of neologisms (Pembra, Burrolvo, Jacapardo, Giramiga and Tubaraco). On the other hand, in the attribution of the gender value, it was verified, mainly through the students' speeches in the accomplishment of the task, that these were based on the alternation of the thematic index. That is, neologisms like Pembra and Giramiga are of the feminine gender, since the thematic index is -a; and the neologisms Burrolvo, Jacapardo and Tubaraco are male gender, since the thematic index is -o. Therefore, it is concluded that students are wrongly based on the alternation of the thematic index for the attribution and identification of the gender value of the nouns.

Nevertheless, in three groups of students, different categories of sex were attributed to the same animal (Fonhoca, Dorinha and Camedo). As an example, in the imaginary animal named Fonhoca, one of the students of the group considered that it was a female referent, while another indicated that it corresponded to a male referent. Thus, in the first case, the student apparently had as reference the gender value of the neologism for the attribution of the category sex; in the second case, the student, although he may have concluded that the neologism in grammatical terms was in the feminine gender, did not take it into account for the attribution of the category of sex. Therefore, in relation to the latter case, it becomes possible to place the hypothesis that the student is not moulded by the formal teaching of the nominal gender category. This teaching tends to defend the existence of a close relation between linguistic gender and the biological sex of the referents, being based, therefore, on erroneous and outdated conceptions, which inevitably will be mirrored in the representations and the knowledge constructed by the students.

Table 2 - Attribution, on the part of the students, of the sex of the referents named by the neologisms

In conclusion, the data presented confirm that there is still a clear confusion between linguistic gender and biological sex of referents. This confusion lies in teaching materials, such as school course books, and often in teachers' own pedagogical discourse, reflecting and shaping the representations and knowledge that are built up in students. Therefore, it is of utmost importance that the teacher builds and develops an in-depth (meta)linguistic knowledge based on disciplines such as Linguistics, Applied Linguistics, History of Language and Educational Linguistics, and constantly updated (Leal, 2009); with the purpose of filling wrong and outdated conceptions that prevail in teaching.

4. CONCLUSIONS

Considering the study we have just presented, it is important to mention that the data collected through direct observation and final products confirmed that the use of ICT were a motivational factor in the teaching and learning processes, ensuring a growing involvement of students activities. In fact, this pedagogical strategy encouraged the students to want to learn, even promoting satisfaction in the teaching and learning processes. Therefore, ICT investment in the creation of digital learning contents (Leite & Ribeiro, 2012) has stimulated the children's motivation for the same and creates spaces for interaction and sharing, supporting learning and making the teacher as a technological innovator. In addition, ICT has appeared as a pedagogical strategy for the development of competences in the field of language teaching, especially the development of the components involved in reading comprehension.

In addition, in the grammatical contents highlighted in this text, the renewed and consistent (meta)linguistic knowledge that a Portuguese teacher must possess is relevant in order to, in a general way, bridge the confusion between linguistic gender and biological sex and the teaching of the verb mainly in terms of syntactic subclasses, ignoring its semantic value and the multiplicity of situations that this class of words can express.

REFERENCES

Andrade, E. (1999). Aquela nuvem e outras. Porto: Campo das Letras.

Baptista, A. et al. (2013). Representação e Aquisição do Género Linguístico em PE: alguns contributos a partir da análise de materiais pedagógicos. In Atas do IV Simpósio Mundial de Ensino da Língua Portuguesa. Língua Portuguesa: ultrapassando fronteiras, unindo culturas. Goiânia: Faculdade Letras da Universidade Federal de Goiás.

Brito, A. M. (2003). Categorias sintácticas. In M. H. Mateus et al. (Aut.), Gramática da Língua Portuguesa (323-432). Lisboa: Editorial Caminho.

Cain, K. & Oakhill, J. (2009). Reading Comprehension Development from 8 to 14 years. The contribution of component skills and processes. In R. K. Wagner, C. Schatschneider & C. Phythian-Sence (Eds.). Beyond Decoding. The Behavioral and Biological Foundations of Reading Comprehension (143-176). New York: The Guildford Press.

Choupina, C. (2017). Aspectos estruturantes da morfossintaxe da LGP: expressão da quantidade e das categorias de sexo dos referentes animados. Revista Leitura, 1, (58), 4-25.

Choupina, C. (2015). Particularidades da sintaxe dos predicados verbais e do ensino da transitividade no 2.º Ciclo EB. Exedra. Revista Científica. Didática do Português. Investigação e práticas, Número Temático, 353-382.

Choupina, C. et al. (2016). Conhecimentos e regras explícitos e implícitos sobre género linguístico nos alunos dos 1.º e 2.º Ciclos do Ensino Básico: a influência da classe formal do nome. Revista da Associação Portuguesa de Linguística, 1, 121-150.

Choupina, C., Baptista, A. & Costa, A. (2014). A gramática intuitiva, o conhecimento linguístico e o ensino-aprendizagem do género em PE. In Anais do IV SIEL - Simpósio Internacional de Ensino da Língua Portuguesa,

Uberlândia, 8-10 Out., 2014.

Costa, J. A. & Choupina, C. (2011). A história e as histórias do género em português: percursos diacrónicos, sincrónicos e pedagógicos. Coimbra:

Escola Superior de Educação.

Costa, J. A. et al. (2015). Género gramatical: a complexidade do conteúdo e a sua abordagem nos documentos reguladores do ensino do Português no 1º Ciclo EB. Exedra: Revista Científica. Didática do Português. Investigação e práticas, número temático, 1, 321-352.

Cunha, L. (2004). Semântica das Predicações Estativas para uma Caraterização Aspectual dos Estados. Porto: Faculdade de Letras.

Decreto-Lei n.º 6/2001 de 18 de janeiro. Diário da República n.º 15 – I Série A.

Ministério da Educação. Lisboa. Reorganização curricular do ensino básico.

Dicionário Terminológico (2008). Acedido a 20 de março de 2019 e disponível em http://dt.dgidc.min-edu.pt/.

Duarte, I. (2003). Aspectos linguísticos da organização textual. In M. H. Mateus et al. (Aut.), Gramática da Língua Portuguesa (85-126). Lisboa: Editorial

Caminho.

Duarte, I. & Brito, A, M. (2003). Predição e classes de predicadores verbais. In M.

- Mateus et al. (Aut.), Gramática da Língua Portuguesa (179-203). Lisboa: Editorial Caminho.

Duarte, I. & Oliveira, F. (2003). Referência nominal. In M. H. Mateus et al. (Aut.), Gramática da Língua Portuguesa (205-272). Lisboa: Editorial Caminho.

Ducla Soares, Luísa (2010). Meninos de todas as cores. Lisboa: Edições Nova Gaia.

Faria, I. H. (2003). O uso da linguagem. In M. H. Mateus et al. (Aut.), Gramática da Língua Portuguesa (57-84). Lisboa: Editorial Caminho.

Figueiredo, V. (1999). Fala Bicho. Alfragide: Editorial Caminho.

Flores, P., Escola, J. & Peres, A. (2009). A tecnologia ao Serviço da Educação: práticas com TIC no 1º Ciclo do ensino Básico. In VI Conferência Internacional de TIC na Educação – Challenges (715-726). Braga: Universidade do Minho.

Giasson, J. (1993). A Compreensão na Leitura. Porto: Edições ASA.

Gonçalves, A. & Raposo, E. (2013). Verbo e Sintagma Verbal. In E. Raposo, M. F. Nascimento, M. A. Mota, L. Segura & A. Mendes (Orgs.), Gramática do

Português, Vol. II (1155-1218). Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

Gouveia, M. C. (2004). Considerações sobre a categoria gramatical de género. Sua evolução do latim ao português arcaico. Biblos, n.s. II, 443-475. Coimbra: Faculdade de Letras.

Leal, S. (2009). Ser professor… de Portugues: Especificidades da formação de professores de língua maternal. Actas do X Congresso Internacional Galego Português de Psicopedagogia (1302 – 1315). Braga: Universidade do Minho.

Leal, T. F. & Roazzi, A. (1999). Uso de pistas linguísticas na leitura: análise do efeito da consciência sintático-semântica sobre a compreensão de textos.

Revista Portuguesa de Educação, 12 (2), 77-104.

Leite, C. (2012). A articulação curricular como sentido orientador dos projetos curriculares. Educação Unisinos, 16 (1), 87-92.

Leite, W. & Ribeiro, C. (2012). A inclusão das TICs na educação brasileira: problemas e desafios. Magis, Revista Internacional de Investigación en Educación, (Online), 5 (10), 173-187. Disponível em http:// www.redalyc.org/pdf/2810/281024896010.pdf.

Lencastre, L. (2003). Leitura: a compreensão de textos. Lisboa: Fundação

Calouste Gulbenkian.

Letria, J. J. (2009). A Minha Primeira República. Lisboa: Dom Quixote.

Letria, J. J. (2005). O Alfabeto dos Bichos. Alfragide: Oficina do Livro.

Lopes, A. S. (2018). Diálogos entre conhecimentos científicos e cientificopedagógicos na formação do professor de português nos 1.º e 2.º CEB. Relatório de Estágio. Escola Superior de Educação, Porto, Portugal. Retirado de http://recipp.ipp.pt/handle/10400.22/12095.

Lopes, A. S., Choupina, C. & Monteiro, S. (2017). A formação do professor de 1.º CEB: como articular conteúdos de Português e de Estudo do Meio?. In. L. G. Correia, R. Leão & S. Poças (Orgs.), O Tempo dos Professores (499-513).

Porto: CIIE - Centro de Investigação e Intervenção Educativas/Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências da Educação da Universidade do Porto.

Mateus, M. H. et al. (2003). Gramática da Língua Portuguesa (5.ª ed.). Lisboa: Caminho.

Melo, P. (2017). Propriedades Sintáticas e Papéis Semânticos do Sujeito em Orações Escritas. Revista Científica Trama, 13 (30), 191-211.

Oliveira Martins, G. et al. (2017). Perfil dos Alunos à Saída da Escolaridade Obrigatória. Lisboa: Ministério da Educação.

Perfetti, C., Landi, N. & Oakhill, J. (2005). The Acqusition of Reading Comprehension Skill. In M. J. Snowling & C. Hulme (Eds.), The science of reading: A handbook (227-247). Oxford: Backwell.

Plano Nacional de Leitura (2017). Quadro Estratégico. Plano Nacional de Leitura 2027. Lisboa: PNL.

Pombo, O. (2005). Interdisciplinaridade e integração dos saberes. In Liinc em Revista, 1 (1), 3-15.

Ponte, J. P. (2002). As TIC no início da escolaridade: Perspectivas para a formação inicial de professores. In J. P. Ponte (Org.), A formação par a integração das TIC na educação pré-escolar e no 1º ciclo do ensino básico (19-26). Porto: Porto Editora.

Ribeiro, I. et al. (2010). Compreensão da leitura. Dos modelos teóricos ao ensino explícito. Coimbra: Almedina.

Roldão, M. C. (1999). Gestão Curricular – Fundamentos e Práticas. Lisboa: Ministério da Educação – Departamento da Educação Básica.

Rothstein, S. (2008). Telicity, Atomicity and the Vendler Classification of Verbs. In S. Rothstein (Ed.), Theoretical and Crosslinguistics Approaches to the Semantics of Aspect (43-78). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Torrado, A. (1994). O mercador de coisa nenhuma. Porto: Civilização. Viana, A. M. (2008). Bichos Diversos em Versos. Alfragide: Texto Editores.

Viana, F. L. et al. (2010). O Ensino da Compreensão Leitora. Da Teoria à Prática Pedagógica. Um Programa de Intervenção para o 1.º Ciclo do Ensino Básico. Coimbra: Edições Almedina.

Villalva, A. (2003). Estrutura Morfológica Básica. In M. H. Mateus et al. (Aut.), Gramática da Língua Portuguesa (917-938). Lisboa: Caminho.

[1] “transversal key component” (translation of the original in Portuguese).

[2] "a semantic predication and a syntactic predication about an entity - the subject" (translation of the original in Portuguese).

[3] "gender is an arbitrary category and, therefore, does not correlate with the notion of sex" (translation of the original in Portuguese).

[4] "biological sex functions as a motivation for the attribution of gender value" (translation of the original in Portuguese).

[5] Study of the Environment is a subject of Primary Education in Portugal, which is dedicated to the study of themes related to the Humanities and Social Sciences and the Physical-Natural Sciences.

[6] "existence of areas disciplinary and non-disciplinary curricula aimed at achieving meaningful learning and the integral formation of students through the articulation and contextualisation of knowledge." (translation of the original in Portuguese).