Artigo Completo

A multi-stakeholder approach to sustainable rural tourism development: the heritage trail of Dolenjska & Bela krajina Case Study

Marko Koščak

University of Ljubljana

Tony O’Rourke

University of Stirling

ABSTRACT

One of the beneficial methodologies for growing and developing a level of tourism, which is sustainable and enhances the totality of local and regional environments, is a multi-stakeholder approach to tourism development. In this paper, we propose that sustainable rural development takes an integrated approach in the development process, supported by and benefiting from a core of multiple stakeholders. It is clear that: a) Entrepreneurship, in a bottom-up model may have a huge impact on rural micro-economies at a local level. It drives wealth creation and expands employment in a measurable, tangible and transparent way; b) Multi-stakeholder tourism projects benefit ownership transformation processes by forcing public, private, and social entities to work for the common benefit. Because of the bottom up approach the measurable value is also more obvious; c) By engaging local public agencies, the dimension of environmental planning and protection can be assured. In this way the sustainable nature of tourism and its impact on the local environment can be assessed and given due priority. D) At the same time, entrepreneurs comprehend the value of co-operation. An integrated model enables participants to benefit from the totality and complexity of resources and skills held by all stakeholders.

Palavras-chave: multi-stakeholder approach, Dolenjska & Bela krajina, Slovenia, bottom-up approach, integrated project, heritage trail

THE MODEL & ASSOCIATED DEFINITIONS

Clearly the model we are referring to, as demonstrated in the Case Study utilised in this paper, has a very precise local/regional orientation. The Heritage Trail of Dolenjska & Bela krajina Case Study has a rural base and is profoundly affected by the need to attract tourism inputs without damaging the sensitivities of the rural environment. It also has a strong multi-stakeholder approach which in many ways illustrates the impact in EU-funded programmes of the concept of subsidiarity - aiming at seamless connectivity between EU supranational policy and funding, member state objectives in macro-economic harmonisation and stabilities and local micro-economic needs.

It has been demonstrated that the concept of sustainable development has grown out of a heightened environmental awareness. The environment is essential to all of us, and therefore a shared concern for everyone, which is why it can be argued that everyone must participate in its conservation. More recently, it is becoming widely recognised that bringing solutions to the vast range of development problems is immensely complex and that it will require a much broader-based approach, if solutions are to be effective. One theme in particular, which emerges from the review of sustainable development and tourism literature provided here, is that, in order to achieve increased sustainability, many advocate greater involvement of stakeholders in decisionmaking about development options and particularly through the formation of partnerships.

Within tourism literature and practice, a wide range of terms are used to infer inclusivity or participation, including alliances, coalitions, forums, and task forces. Over recent years the notion of ‘partnership’ has become particularly prevalent. It is a term that is used particularly by the government and practitioners to describe regular, sometimes cross-sectoral, interactions between groups who aim to achieve a set goal or policy objective. Partnership is seen as a “long-term relationship based on a common cause and mutual respect for each stakeholder’s mission and values” (Presas, 2001, p. 208). Partnerships are believed to have the potential to promote discussion, negotiation, and the building of mutually acceptable proposals about how tourism should be developed (Hall, 2000; Healey, 1997). Furthermore, partnerships can also reflect and help protect the interdependence between tourism and other activities and policy areas. Partnership is desirable in order to secure what Huxham (1993) describes as “collaborative advantage” — the realisation of an objective that no single organisation could achieve on its own. There are three main reasons to consider partnership (Hasting, 1996): to foster inclusivity, to achieve integration of ‘crosscutting’ issues, and to ensure more efficiency in service delivery.

In developing a case study which discusses the development of tourism within a sustainable rural environment, we are including within this concept of sustainable rural tourism the following areas:

- cultural & heritage tourism;

- vinicultural & gastronomic tourism;

- ecological tourism;

- active & adventure tourism.

- Furthermore, we should also make clear that in general we see three main groups of actors engaged in the multi-stakeholder model:

- The public sector - by this we mean municipal/local government, state agencies and international organisations operating in a local or regional framework;

- The private sector - by this we mean privately owned enterprises, including quoted or unquoted companies, as well as partnerships or self-employed individuals;

- The social sector - by this we mean entities established for mutual benefit, including co-operatives, community interest associations, not-for-profit agencies and societies.

1. INTRODUCTION

The rural case-study presented is one of a region in Slovenia along the border with Croatia ((see Figure 1), where we track a fifteen year process, from preliminary idea - to the operational reality of sustainable international tourism in a strategically-located destination-region.

Figure 1 - Geographic position of Slovenia in EU and the region of Dolenjska and Bela krajina in Slovenia (Source: Author’s archive)

In the case of the Slovenia example explained in the case study, an additional factor is the multiple dynamic of international, national, regional and local agencies involved in the project. These were drawn from public, private and social sources, but the key actors and catalysts who can be identified in this story were the Slovenian Ministry of Agriculture, Slovenian Ministry of Economy, the Bavarian State Ministry for Agriculture, the Faculty of Architecture in Ljubljana, the European Commission’s Tourism Directorate, a Regional Chamber of Commerce in Dolenjska and Bela krajina, a commercial tourism operator, and at later date, an international market research consultant.

2. INTEGRATED RURAL COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PROJECT

The CRPOV Programme (Integrated Rural Development and Village Renovation), which commenced in 1990, was associated both with the UN Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and with the Bavarian Ministry for Agriculture. Bavaria helped in the initial phase transferring experience and know-how. CRPOV was based on a bottom-up approach, involving an initial 14 local project-areas, starting in 1991. Two of the project villages were located in the Slovene municipality of Trebnje with around 500 local residents involved in the project. During this period some 250 local projects were developed in Slovenia, primarily aimed at development possibilities for rural economic diversification (Koščak, 2002).

The community development role of CRPOV involved many local village meetings, linked to the economic need for diversification of the rural economy. CRPOV worked together with an expert team on strategy and action. Critically, this case-study relates to a rural region which sits strategically between Ljubljana and Zagreb, on the international motorway from Belgrade to Ljubljana. This has a high location potential for selling locally-sourced food and wine products, as well as craft and tourism products. Tourism is based on the appeal of a gentle landscape of hills and river-valleys - for walking, horse-back riding, cycling, angling, rafting, or the simple enjoyment of its unspoilt character (Koščak, 2009).

The CRPOV, as an Integrated Rural Community Development programme, led the way towards rural product development, and as a by-product, communitybased sustainable tourism. Such tourism requires partnership and co-operation between the public, private and the NGO voluntary sectors. Co-operation of this sort was not common in the period 1992-1995 in Slovene tourism. It was clear, however, that sustainability -in Slovenia or anywhere else - requires community involvement together with the firm the commitment of local actors and producers of products and services. The appeal of such action is to add tourism products to the other rural products, which they complement. For successful performance of the Slovene tourism offer in global tourism markets, partnerships and clear targets remain crucial. People living in the destination represent a key advantage and are also an aid to competitiveness. The social capital of tourism networks is of highest importance in the process of creating tourism development. In the concept of social capital there was at first a strong emphasis upon the social capital of individuals, but later it was realised that development of human capital, and the economic activity of businesses, geographic regions and nations were all important (idem).

3. INTERNATIONAL TEAM HERITAGE TRAIL CONSULTANCY

This background of the CRPOV programme as well as the parallel development in terms of Wine Trails, prompted the Regional Chamber of Commerce of Dolenjska & Bela krajina to accept an invitation by a consortium (which had in 1996 secured European Union funding to launch two pilot projects in Slovenia and Bulgaria) to create Heritage Trails. The consortium included Ecotourism Ltd. (a British consultancy firm), PRISMA (a Greek consultancy firm) and ECOVAST (The European Council for the Village and Small Town). All of these were supported by regional and national institutions in the field of natural and cultural heritage.

Involvement of stakeholders in strategic management of a destination is important in each stage of development. The research shows the importance of cooperation of key stakeholders (i.e. civil society, private sector, public sector) at different levels. Moreover, we would like to demonstrate the importance of the ‘bottom-up’ development in a destination, which we can frequently interpret as a pressure on public institutions and the public sector, i.e., for additional infrastructure building.

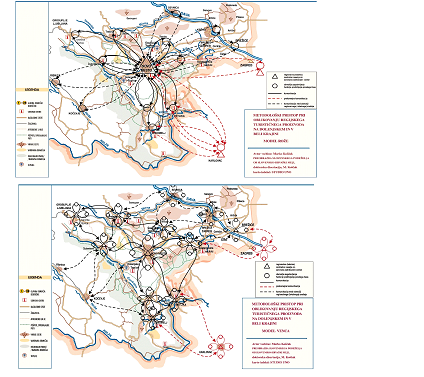

The UK/Slovene Heritage Trail team conducted a ‘Tourist Resource

Inventorisation & selection’, based upon natural, built and living cultural heritage resources in the selected region. Some 150 sites were identified and proposed by the different partners involved in the participation process for the Heritage Trail. From this large number, 28 sites were selected, to be networked in a trail system for the area. The idea was to develop a tourist product which was capable of offering opportunities for stays off up to seven days in the region. Two key access-forms were used for the clustering of attractions, one a “flower structure”, and the other a “garland structure” (see Figure 2). Existing tourist assets and potentials were the basis of these groupings (Koščak, 2009).

Figure 2 - Flower and Garland model, (Source: Author’s archive)

A major result of this work was the creation of a Regional Partnership of 32 organisations, from the public, private and NGO sectors, which signed an agreement to co-operate in the Heritage Trail’s implementation phases of marketing and product development. This partnership - working under the umbrella of the Regional Chamber of Commerce – was in operation for 12 years, and was in 2009 transformed into the LEADER Local Action Group – LAG responsible for overall rural development in the region of SE Slovenia including sustainable tourism. The partnership supports, co-ordinates and brings together the provider-partners. Work in general consists of marketing activities, product development, and training activities, where different combinations of partners, institutions, and individuals are involved.

For marketing purposes, a local commercial partner - Kompas Novo mesto - was invited into the partnership in 2001, in order to articulate a stronger and more effective assault on foreign markets. Kompas was engaged to act as the marketing agency, on behalf of the Heritage Trail partnership. Although the official launch of the product was in 1997, at the World Travel Market in London, followed in 1998 by a presentation at ITB/Tourist Fair in Berlin, there was no significant response. Foreign markets at that time had limited awareness about any Slovene tourist products, other than what can be described as the constantly featured traditional Slovene Tourist icons, such as: Lake Bled, Kranjska Gora ski resort, Postojna Cave, and Portoroz seaside resort (Travis 2003).

The effective commercial launch of the Heritage Trail at an international level, with a foreign tourist industry adviser and a much greater professionally coordinated national approach, was delayed until 2002 in London. There, at the World Travel Market, the launch had the active support of the Slovenian Tourism Board, together with other relevant institutions.

4. STAGES OF COMMERCIAL PRODUCT ADAPTATION, AND IMPLEMENTATION

In Slovenia, the issue of collaborative planning has been addressed in the Strategy of Slovenian Tourism from the year 2007 onwards (Jegdič, Tomka, Knežević, Koščak, 2016). At that time defining inter-regional connectivity was seen as an important task. The strategy of the year 2007 implemented the need for inter-destination connectivity and cooperation. However, the regional destination organisation did not become a new administrative structure, or a new organisational body, but it only changed its functional form. The most general aim was stated to be to encourage entrepreneurship by enabling easier economic use of new ideas and to encourage the foundation of new companies. As it is visible from this formulation, it is a completely generalised aim that is focused on wide conditions of business that apply to all areas of economic development, not only to tourist development. In that context, special emphasis is placed on the development of small and medium sized businesses, a goal that was especially interesting to the previous administration of the European Commission, and it seems that it remains a “mantra” in the institutions of that organisation.

Nevertheless, the problem revealed that although there is much interest in Slovenia as a high-growth destination country, it was seen by the international industry as one with 3 major attractions – the ‘tourism icons’ already mentioned – lakes and mountains, caves and sea. For a significant period of time, Slovene overseas marketing has tended to focus only on these well-known destinations.

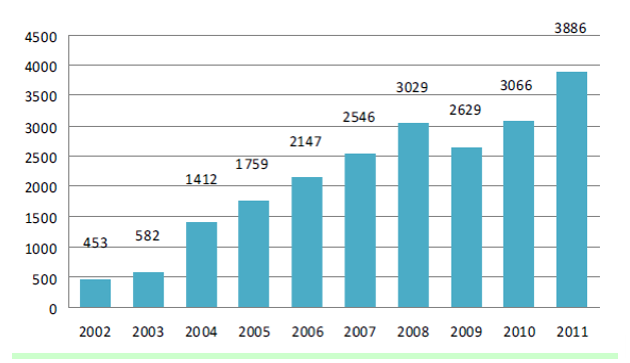

By 2003, low-cost airlines made Slovenia easily accessible to high-spend markets. Air travel cannot be a basis for sustainability, but may be used as the initial opening up phase for a new destination or product in the first place. Ultimately, connected rail travel access must be the longer term primary aim. However, as this initial stage of opening the Heritage Trail market (see Figure 3), the transport access methodology was via the low-cost airline destination airports of Ljubljana (Easyjet), Klagenfurt (Ryanair) and Graz (Ryanair), with access ground transport routing via Ljubljana. In-depth contact with key operators by phone showed that there were two viable special-interest packages, which could appeal commercially-speaking (Travis, 2003):

a) A Heritage Trail Add-On Package to offers at Bled (Lakes & Mountains) or Ljubljana (City & Culture)

b) An Integrated new 'Highlights of Slovenia' holidays, which started with 25% of their time at two existing icons (Bled & Ljubljana), then the remaining 75% of the time allocation spent on the Heritage Trail

Testing of this product with a group of six UK travel professionals was extremely successful. A second tour with tour-operators from Germany and the UK in 2004 was less successful. In 2005, a specialist walking-tour firm assembled its bespoke and individualised Heritage Trail offer, and at the time of writing, Independent Tour Operator firms were preparing for launching on-line, two individualised alternative packages.

Figure 3 - Volume of visits to Heritage Trails product from 2002 – 2011 (Source: KOMPAS Novo mesto, 2012)

5. HERITAGE TRAILS AND CREATIVE INDUSTRIES: IN GENERAL AND IN CASE OF DOLENJSKA AND BELA KRAJINA DEVELOPMENT

We have also examined international issues where we noted a greater shift towards the values of sustainability and environmental protection in tourism activity. We emphasise that tourism requires to be sustainable by promoting longterm benefits and enhancing the cultural and environmental heritage.

Creating a visitor profile of the kind of tourists interested in natural and cultural heritage tourism is very difficult due to their diversity of interests and the general lack of targeted market research. Thus, only general comments can be given here, based on the results of practical experience in different tourism destinations. Tourists in search of natural and cultural heritage seem to look for a wide range of different attractions and activities designed to satisfy different needs, namely: learning, relaxation, recreation or adventure, amongst others. The following are some examples of activities that can be developed using natural and cultural heritage and are related to cultural tourism (Koščak, 2012):

- festivals and events, banquets;

- music, theatre, shows;

- village life and rural life (e.g. farms, Sunday markets,);

- gastronomy, visiting/tasting local products;

- general sightseeing, village buildings and ‘atmosphere’ ;

- visiting historic and religious monuments or vernacular buildings, ruins; – famous people in the region.

It is also worth mentioning that nature and culture orientated tourists are also strongly influenced by the quality and type of accommodation and food on offer. It seems that tourists in search of nature or culture are rarely attracted to large luxury hotels. They will be much more interested in smaller establishments of good quality, which provide a personal service and a certain level of comfort and quality - the demand for two and three star accommodation is generally very strong. There is also a small but growing proportion of tourists looking for character and charm in their accommodation. Rural accommodation, family hotels and pensions that use local quality crafts or are located in vernacular buildings are becoming increasingly popular. However, there are a number of additional factors that should be taken into consideration when dealing with natural and cultural heritage:

- Cultural and the environmental heritage cannot be produced: They exist because of history and geography and cannot be created easily in the short term. This means that destinations need to work with what they have. If their intrinsic appeal is low or only moderate, it will be very difficult for the area to gain a competitive edge over other destinations.

- Cultural and natural attractions are mostly a public resource: Tourists rarely have to pay to see nature and most of culture – e.g. to visit nature reserves, landscapes, village architecture… It is therefore mostly the private businesses, who develop a derived product around this public resource, that reap the economic rewards. But there is no automatic mechanism for ensuring that some of this income is put back into maintaining and enhancing the cultural and natural heritage itself.

- Damage to natural and cultural resources are extremely difficult to measure: Tourism inevitably impacts on the natural and cultural resources of a particular destination but its interrelationship is extremely complex and very difficult to quantify. There is no universal formula for determining carrying capacities for sites (i.e., the number of people that can visit the site without causing significant damage to it) as so much depends on the particular circumstances of the area.

- Finally, the pricing structure of heritage-based tourism is not as clear as in other services or other forms of tourism. There is little guidance available in this area due to the lack of established benchmarks. Comparable attractions in other regions might exist but in a different economic climate which makes comparisons difficult. Consequently, businesses might be pricing themselves out of the market, or more likely undercharging. Different local thematic routes, such as wine, fruit, cheese and others, were created, in which local entrepreneurs started to create new tourism products and through the marketing of HT partnership offer them on domestic and international markets. All above mentioned activities were conducted and implemented by HT partnership institutions, Chamber of Agriculture, which was responsible for the organisation of all trainings and certification based on the national curriculum for supplementary activities and Regional Development Agency. This offers support and expertise in providing know-how on business plans and other entrepreneurial activities needed for application on tenders of various EU funding.

Already at a very early stage of HT development number of initiatives were taken in order to support and encourage individual and private sector to become important part of this development. Major idea behind was to create opportunities for new jobs and economic diversification in rural parts of Dolenjska and Bela krajina, SE region of Slovenia. With such initiatives and support of HT partnership in providing funding, some 600 individuals took different type of education and training such as meat and milk processing, bakery, bee-keeping, wine production and its marketing, tourist guiding, fruit drying on traditional way, and many others. All these individuals received certificates, which allow them to open their individual business and on one side satisfy all legislative requirements and on the other side apply for further funding from Rural Development Programmes offered by the fact that Slovenia joins EU in 2004.

Different local thematic routes, such as wine, fruit, cheese and others, were created, in which local entrepreneurs started to create new tourism products and through the marketing of HT partnership offer them on domestic and international markets. All above mentioned activities were conducted and implemented by HT partnership institutions, Chamber of Agriculture, which was responsible for the organisation of all trainings and certification based on the national curriculum for supplementary activities and Regional Development Agency. This offers support and expertise in providing know-how on business plans and other entrepreneurial activities needed for application on tenders of various EU funding.

After this initial stage of certification, which was important in order to assure that business will operate on legal ground as well as according to new EU regulation and requirements, a next stage of more innovative and robust initiatives took place. Some individuals and even group of partners decided to develop new product which has traditions back in past and give them fresh and new outlook, as required on modern EU tourism markets (The Gallup organization, 2011).

6. THEMATIC ROUTES – NEXT STAGE DEVELOPMENT…

From these well accepted initials we seek for further development of the product. Our thinking was led by the facts that:

- More than 75 % of tourist from foreign markets are seeking the active holidays,

- More than 50 % of the reservations are made by internet,

- More tourists want to change the destinations every couple of days, etc. (Koščak, 2012)

So, we find out that we have to create the product which:

- can be used by individual traveller in the same manner than by tour operator;

- will connect actual tourist offer in the region;

- will be supported by all new common and used technologies;

- will support active holidays;

- should be different than other products in the field of active holidays.

In 2009 and with financial support of the European Regional fund we successfully finished the project, which fulfil all that conditions.

With the project we built “back-bone” for four main activities hiking, biking, horse riding and rowing in the whole region (see Figure 4 below). The routes are connecting natural and cultural heritage of the region with other tourist offer, such as accommodation, activities, information, services, etc. (Koščak, 2012).

Figure 4 - the Heritage Trail portal (Source: http://www.slovenia-heritage.net)

Wholly digitalised and located by GPS, routes are now presented in the renewed portal http://www.slovenia-heritage.net/ and the new built mobile portal http://activeslovenia.mobi. The product can also be found on facebook and YouTube platforms. Biking and horse riding routs can also be found. The potential tourist can detail look and plan its holidays from home (through the internet). Once on the terrain, they can use Mobile, PDA, GPS devices (and print outs) to navigate himself on the region. For those who don’t have enough time to create the holidays by themselves, the active tourist packages are (pre-)prepared and shown on the web as well.

KEY LEARNING POINTS

- It is evident from the Case Study that the Heritage Recycling for Tourism phase was preceded by the work on Integrated Rural Community Development. This stimulated a community-based approach to development, in which context tourism was a part of the economic mix. This created a real hope of sustainability via the local communities support for a new mixed economy, thus indicating that sustainable development can underpin successful tourism, if the correct strategy is chosen;

- The evidence from the project has also made clear that heritage-resource based tourism development, if it is to be sustainable, must a) show respect for the carrying capacity of resource-zones - be they robust or fragile and b) have rural community involvement and commitment to tourism, because they have a stake in it, and have net gains from it;

- Much tourism development arises because the destination creates potential tourism products, due to the fact that they wish economic gain from them. Rural tourism products have to be adjusted to fit niche market demands that are highly competitive sectors internationally. Thus, market awareness and understanding must be built-in early in the development process, or it becomes much longer and harder;

- New tourist destinations are very difficult to launch internationally, even if they have high accessibility, unless they can be linked and tied in to existing tourism icons or magnets. This new Slovene offer had to be adjusted to do just that;

- The "gateway" identification is critical in new product formulation. Whether this be a selected airport, seaport, railway station or whatever. If the gateway is the airport of an attractive heritage city (such as Ljubljana), then both addon package possibilities, as well as links to a popular 'short-city break' destination, add great value;

- Continuity of personnel in a development process is of real importance. The role of the Project Manager in initiation and continuity is critical, and the continuing interactions with external partners - who are supportive and share a belief in the integrity of the development, over the long term – is also valuable;

- This model ultimately is one of community-based multiple-stakeholders, having the equal support of small rural operatives and major agencies. The support from several levels: local, regional, national, and international, have enabled the thirteen year development-cycle of the Dolenjska-Bela Krajina HT project to be achieved.

CONCLUSION: CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS

There are good reasons why the Slovene Heritage Trail model is being successfully adopted in several neighbouring countries as an initiative for rural regeneration through sustainable tourism, namely:

Factor 1 - Sustainable & responsible tourism

A heritage trail focuses on the natural and cultural assets of a rural region. This runs the risk of exposing some of the most vulnerable sites in a region to excessive numbers of tourists. The preparation of a heritage trail, therefore, must include a tourism “carrying capacity study” at each proposed tourism site. If a sudden increase in tourists risked damaging the physical or natural attributes of a site, or if it were to exceed the tolerance of the local people, it should not be included in the heritage trail until preventive measures can be implemented.

Factor 2 - Complementing other tourism products

Although a heritage trail focuses on only some of the attractions of a region, it can be complementary to other tourism products on offer. For example, it can contribute to economies of scale in regional promotion - in Slovenia, the heritage trail and spa tourism were promoted jointly, and costs of this shared. A heritage trail can also contribute to a wider choice of products for target markets. Taking the example of Slovenia again, spa tourists may be interested in the heritage trail product, and heritage trail tourists may enjoy the spa facilities.

Factor 3 - Economic regeneration

A heritage trail is created as a tool for rural economic regeneration. The heritage trail extends tourism from existing centres into new and undervisited areas, by increasing the number of visitors, extending their stay, and diversifying the attractions and services offered to them: expansion, extension and diversification.

Factor 4 - Contributing to regional tourism development

The heritage trail is a tourism product which makes the natural and cultural heritage of a region the focal point of the offering. The development of such a product is, therefore, an integral component of the development of the whole region as a tourism destination. However, a heritage trail is only one product, and many regions have other tourism products on offer which may not be included in the trail. In creating heritage trails in Slovenia, there was frequently a temptation to include all tourism attractions and services in the region. However, if one gave into such a temptation, one would lose the focus of a well defined tourism product.

Factor 5 - Transferability

The heritage trails concept is transferable to other regions and countries, in which there is sufficient natural and cultural heritage to attract tourists and where there is a local desire both to benefit from tourism and to safeguard that heritage. This is particularly the case in parts of central and eastern Europe, where established settlement patterns and rural economies have developed similarly to those in Slovenia.

REFERENCES

Hall, C. M. (2000). Tourism Planning: Policies, Processes and Relationships. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

Hasting, A. (1996). Unravelling the Process of Partnership in Urban Regeneration Policy. Urban Studies, vol. 33, no.3, 253-268.

Healey, P. (1997) Collaborative Planning. Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies. London: Macmillan.

Huxham, C. (1993). Collaborative capability: an intra-organizational perspective on collaborative advantage. Public Money <& Management, 13(3): 21-28. Jegdič, V., Tomka, D., Knežević, M., Koščak, M., (2016). Improving Tourist Offer Through Inter-Destination Cooperation in a Tourist Region. International Journal of Regional Development, 3(1).

KOMPAS Novo mesto. (2012). Unpublished statistical data. Novo mesto.

Koščak, M. (2002). Heritage Trails: Rural regeneration through sustainable tourism in Dolenjska and Bela krajina - Rast, XIII, 2(80), 204-211, MO Novo mesto.

Koščak, M. (2009). Transformation of rural areas along Slovene-Croatian border. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Art, Department of Geography.

Koščak, M. (2012). Po poteh dediščine - od teorije k praksi, Priročnik za načrtovanje trajnostnega razvoja in turizma z vključevanjem naravne in kulturne dediščine s praktičnimi primeri. STUDIO MKA d.o.o..

Presas, T. (2001) Interdependence and Partnership: Building Blocks to Sustainable Development. Corporate Environmental Strategy, 8(3), pp. 203-208.

The Gallup organization, (2011). Survey on the attitudes of Europeans towards tourism. European Commission. Flash Barometer 328.

Travis, S.T. (2003). Market research on Slovenia's key foreign markets. Dolenjska & Bela krajina marketing association, Chamber of Commerce Dolenjska & Bela krajina.